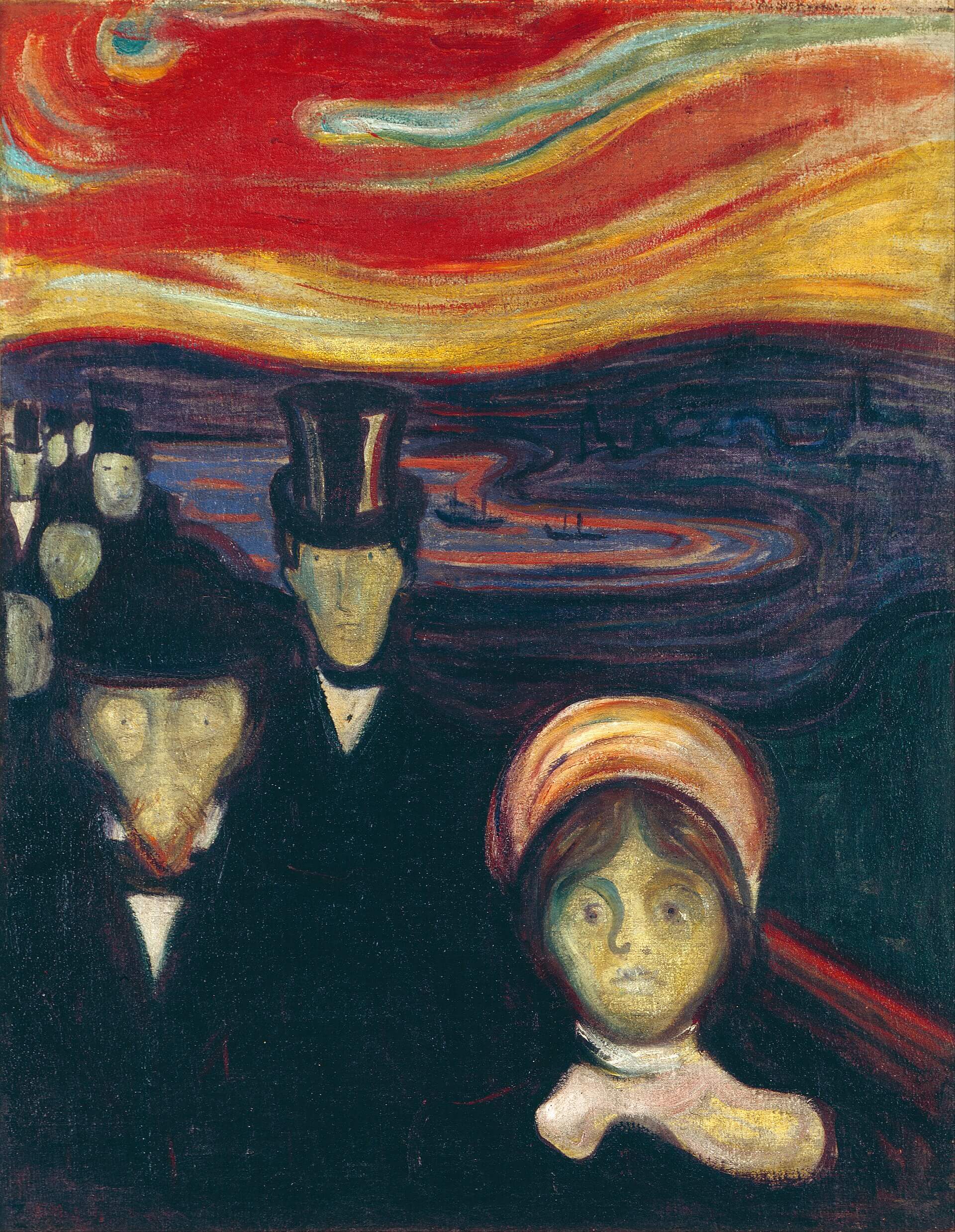

How to Deal With Uncertainty: 3 CBT Techniques to Reduce Worry and Anxiety

An unexpected meeting appears on your calendar. A recruiter stops replying. A loved one doesn’t answer a message for hours.

Nothing bad has happened – yet. Still, your mind races, filling in the blanks, often with the most unsettling explanations.

Unexpected events – pandemics, wars, recessions, layoffs – can leave even the most resilient people feeling unmoored. At the same time, many of life’s most meaningful moments also emerge from uncertainty. We don’t know where we’ll meet a future partner, when an opportunity will arise, or what will happen when we take a risk.

The desire for a predictable, safe life is deeply human. We want our loved ones to be healthy, our work stable, and the future manageable. But reality rarely cooperates. We can control only parts of our own lives, have limited influence over those we love, and little control over larger events. No amount of planning can eliminate uncertainty entirely.

Uncertainty isn’t a failure of preparation; it’s simply part of being alive.

Why Uncertainty Feels Threatening

Uncertainty itself is neutral – it simply means “not knowing.” What makes it feel manageable or overwhelming is how we interpret it.

Some people move through ambiguity with ease. Others find it deeply unsettling. Most of us fall somewhere in between, and our tolerance shifts depending on the stakes, the context, and the moment.

When uncertainty feels intolerable, the brain interprets it as danger. The unknown becomes a problem that must be solved immediately, and events that are merely unclear begin to feel threatening.

Many people cope by trying to eliminate uncertainty – either by increasing control or by avoiding ambiguity entirely.

Trying to Control or Avoid the Unknown

When faced with uncertainty, many of us try to regain control and make situations more predictable. Psychologists call these protective behaviors – strategies intended to reduce anxiety that, paradoxically, often keep it going.

Examples of protective behaviors:

-

Worrying about every possible outcome.

“What if I don’t hear back from the recruiter?” “What if I receive a rejection email?”

-

Overpreparing for even minor decisions.

Spending hours agonizing over a gift for a colleague or double-checking every detail.

-

Focusing obsessively on potential threats and exaggerating them.

“My manager added a sudden meeting; they must be planning to fire me.”

-

Seeking reassurance from others.

“Please tell me everything will be okay.”

-

Insisting on doing everything yourself.

Refusing to share responsibility, convinced only you can do it right.

Avoidance is another common strategy – steering clear of uncertainty entirely. Examples include:

-

Avoiding full commitment. Holding back from friendships or romantic relationships because the outcome is not guaranteed.

-

Declining social invitations or opportunities. Finding reasons not to participate because the situation might provoke anxiety.

-

Procrastinating. Putting off tasks or calls because you cannot predict how they will turn out.

Both strategies are understandable – and both are exhausting. Over time, they teach the mind that uncertainty is dangerous and that control or avoidance is the only path to safety.

Example: Maya

Maya sees an unexpected meeting with her manager on her calendar. Her mind races: “What if my manager is unhappy with my work? What if I get fired?” She spends the day rehearsing every possible scenario, rereading emails, rechecking her work, and drafting talking points “just in case.” That evening, a new friend invites her out – she declines, feeling too unsettled to socialize.

Nothing has gone wrong. Yet uncertainty has taken over.

Maya is trying to reduce anxiety by increasing certainty: thinking through every possible outcome, preparing excessively, and pulling back from unpredictable situations. While these protective behaviors offer momentary relief, they are exhausting in the long run and reinforce the idea that she cannot cope without certainty.

Why These Strategies Don’t Work

Protective behaviors and avoidance may calm anxiety briefly, but over time, they reinforce the belief: I cannot cope unless I eliminate uncertainty.

-

Overpreparing, rehearsing every scenario, or seeking constant reassurance reinforces the idea that we are fragile without certainty.

-

Avoiding unpredictable situations prevents us from discovering whether the feared outcome would actually occur – or whether we could handle it if it did.

Intolerance of uncertainty fuels chronic worry. The more we try to control everything or avoid ambiguity, the less confident we feel in handling life’s inevitable challenges. Yet if we look back honestly, we often realize we’ve survived far more than we feared.

A bit of preparation or caution is wise – but constantly imagining worst-case scenarios deepens worry, narrows our experience, and drains energy.

What Psychology Suggests Instead

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the most well-researched approaches for managing anxiety. Rather than trying to eliminate uncertainty – an impossible task – CBT helps people change how they relate to it.

Three CBT techniques are especially helpful:

-

Recognizing distorted thinking – spotting how your mind exaggerates threats or interprets events negatively.

-

Distinguishing helpful vs. unhelpful worry – identifying worries that help solve problems versus those that trap you in loops.

-

Gradually increasing tolerance for uncertainty – practicing being in situations with unknown outcomes so the mind learns that ambiguity is manageable – and sometimes even positive.

Technique 1: Recognizing the Thinking Errors That Shape Anxiety

Psychologists call repeated, automatic thinking mistakes cognitive distortions. First described by the psychiatrist Aaron Beck, these patterns show how our minds misread reality – especially when under stress.

Cognitive distortions often sneak in so fast we barely notice them. They feel like automatic conclusions: “This is bad,” “I’ve failed,” or “Something terrible is about to happen.”

Common Cognitive Distortions

Catastrophizing

Jumping to the worst possible outcome, even with little or no evidence. Catastrophizing ignores the many neutral or manageable possibilities in between. A small problem becomes a disaster.

-

Your partner says they want to talk, and the mind jumps ahead: They will break up with me.

-

A headache suddenly feels like a serious illness.

Overgeneralization

One negative event becomes proof of a permanent pattern.

-

One bad date → “I’ll always be alone.”

-

One work mistake → “I’m terrible at my job.”

All-or-Nothing Thinking

Seeing experiences in extremes, leaving no room for nuance.

-

You’re either successful or a failure: “If I didn’t do this perfectly, I am a loser.”

-

Either confident or incompetent.

-

Either liked or rejected.

Emotional Thinking

Treating feelings as facts. The emotion becomes “evidence”, even when reality suggests otherwise.

-

Feeling anxious → assuming danger is present.

-

Feeling guilty → assuming you’ve done something wrong.

Mind Reading

Assuming you know what others are thinking – usually something negative – without direct evidence.

-

A colleague seems quiet in a meeting → “They think I’m incompetent.”

-

A delayed reply → interpreted as disinterest or rejection, when the information simply isn’t there.

Labeling

Taking a single action or mistake and turning it into a global judgment about yourself. Instead of describing what happened, your mind declares who you are.

-

Forgetting to mute yourself during a work meeting → “I’m stupid.”

-

Missing a deadline → “I’m irresponsible.”

Personalization

Taking responsibility for events outside your control.

-

A partner seems unhappy → “It must be my fault.”

-

A team project struggles → assuming full responsibility, even when multiple factors are involved.

Mental Filtering

Focusing only on the negative while ignoring the positives. The mind filters out the broader picture, leaving a distorted impression of failure.

- You receive ten positive comments and one critical one → you remember only the criticism.

Disqualifying the Positive

Dismissing or explaining away positive experiences.

-

Success is attributed to luck, not effort.

-

Praise is seen as politeness.

-

Achievements “don’t count” because they don’t fit your negative story.

“Should” Statements

Rigid rules about how life, people, or relationships “ought” to be. When reality doesn’t match these standards, frustration, shame, or resentment often follows.

-

“I should be rich to be successful.”

-

“Parenting should be easy.”

-

“My manager should promote me.”

These are common mental habits, especially when we are tired, stressed, or facing uncertainty. The issue isn’t that these thoughts appear, but that we accept them as absolute truth without question.

The goal isn’t to eliminate them. Instead, it’s to create a pause –a space to ask: “Could there be another way to interpret this?” It’s in that pause that anxiety begins to lose its grip.

How to Help Yourself: Changing Thought Patterns

Step 1: Notice your thoughts

Recognize that thoughts don’t always reflect reality. When you feel anxious, pause and observe your thoughts. Ask: Is this really true? Am I seeing the full picture?

Step 2: Reframe and question

If you spot a distorted thought, look for objective evidence and alternative explanations. Writing down the original thought and a more balanced interpretation can help:

-

“I should be rich to become successful.” → “Success means different things for different people.”

-

“I feel anxious – life is dangerous.” → “Anxiety is just a feeling; it doesn’t make life dangerous.”

-

“They think I am boring.” → “I don’t know what others think until I ask.”

Step 3: Practice patience

Changing thought patterns takes time, awareness, and practice. Each small step of noticing, questioning, and reframing builds confidence in responding to uncertainty with curiosity rather than fear.

Technique 2: When Worry Helps – And When It Doesn’t

Worry is a thought about a potential threat – something that hasn’t happened yet. It often begins with “What if…?”

-

What if the plane crashes while I’m on board?

-

What if my home is broken into while I’m away?

Some worry is helpful. It alerts us to real problems and motivates us to solve them. Other worry is unhelpful. It traps us in mental loops that feel urgent but lead nowhere.

How can you tell the difference?

CBT highlights three key distinctions:

1. Is the problem real or hypothetical – and how likely is it?

-

Helpful worry: Focuses on real or likely problems. Crossing a busy street? Worrying about traffic is reasonable. Facing a visa deadline? Concern motivates you to gather documents, make a checklist, and submit forms on time. Once the steps are done, the worry usually eases.

-

Unhelpful worry: Drifts toward unlikely scenarios. What if the plane crashes? What if I get seriously ill? What if I ruin a relationship? These thoughts feel urgent but rarely lead to solutions.

2. Can I take action to solve it?

-

Helpful worry: Is within your control and leads to concrete steps – a plan, a checklist, or a sensible precaution.

-

Unhelpful worry: Is beyond your control, spinning in your mind without resolution, or drives protective/avoidant behaviors that don’t address the actual problem. Examples: repeatedly thinking, “What if something terrible happens to my partner on the way home?”, constant checking, or seeking reassurance.

3. Does thinking about it help, or just drain you?

-

Helpful worry: Time-limited and proportionate. You think, act, and move on.

-

Unhelpful worry: Lingers, consuming time and mental energy, and often feels uncontrollable. Example: “I have a headache – what if it’s a brain tumor?” and ruminating on it for days*.*

Tip: When worry is unhelpful, more thinking usually makes it worse. Ask yourself: “Is there actually anything to solve right now?” If the answer is no, continuing to dwell only fuels the anxiety.

The most effective response is often disengagement: gently focus on something tangible in the present moment. Thoughts are events in the mind – they don’t require your participation.

Example: Maya

Maya sees an unexpected meeting with her manager on her calendar. Her mind races: What if I’ve done something wrong? What if I get fired?

Then she pauses. The meeting is tomorrow. No urgent emails, no signs of trouble. Worrying won’t change anything.

Instead, she reviews her projects and prepares a few talking points. Her mind feels lighter. The unproductive loop has been interrupted.

Summary: Helpful vs. Unhelpful Worry

| Helpful worry | Unhelpful worry |

|---|---|

| Focuses on real problems or likely situations | Revolves around hypothetical or unlikely scenarios |

| Targets concrete risks: If I cross on red, I could be hit | Magnifies low-probability outcomes: What if this headache is something serious? |

| Leads to practical steps or decisions | Stays in your mind without leading to solutions |

| Usually fades once action is taken | Triggers checking, reassurance-seeking, or avoidance |

| Contained and proportional to the situation | Persists, repeating the same questions without resolution |

Key takeaway: Helpful worry prompts action and then eases. Unhelpful worry keeps you spinning, draining energy, and making the unknown feel more threatening. Recognizing the difference is the first step toward taking back your focus and your calm.

How to help yourself: Distinguishing Helpful vs. Unhelpful Worry

Step 1: Pause and evaluate your worry

When you catch yourself worrying, ask yourself these four questions:

-

Is it about a real, existing problem or a hypothetical one?

-

If it’s hypothetical, is the risk of it happening high or low?

-

Can I do something to address or solve the problem?

-

Is thinking about it helpful, or is it just draining my time and energy?

Step 2: Respond based on the answers

-

Helpful worry: If it’s about a real problem or a likely event, create a concrete plan, a checklist, or take sensible precautions. Once action is taken, your worry usually eases.

-

Unhelpful worry: If it’s hypothetical, unlikely, or beyond your control, it’s unhelpful and will only drain your energy. Shift your attention to tasks that are useful, enjoyable, or meaningful.

Step 3: Observe and let go

Remember: thoughts are just thoughts. You don’t have to follow or act on every one. Simply noticing them and letting them pass can reduce their power. Mindfulness techniques can help create mental distance from unhelpful thoughts, making it easier to stay present and focused on what you can control.

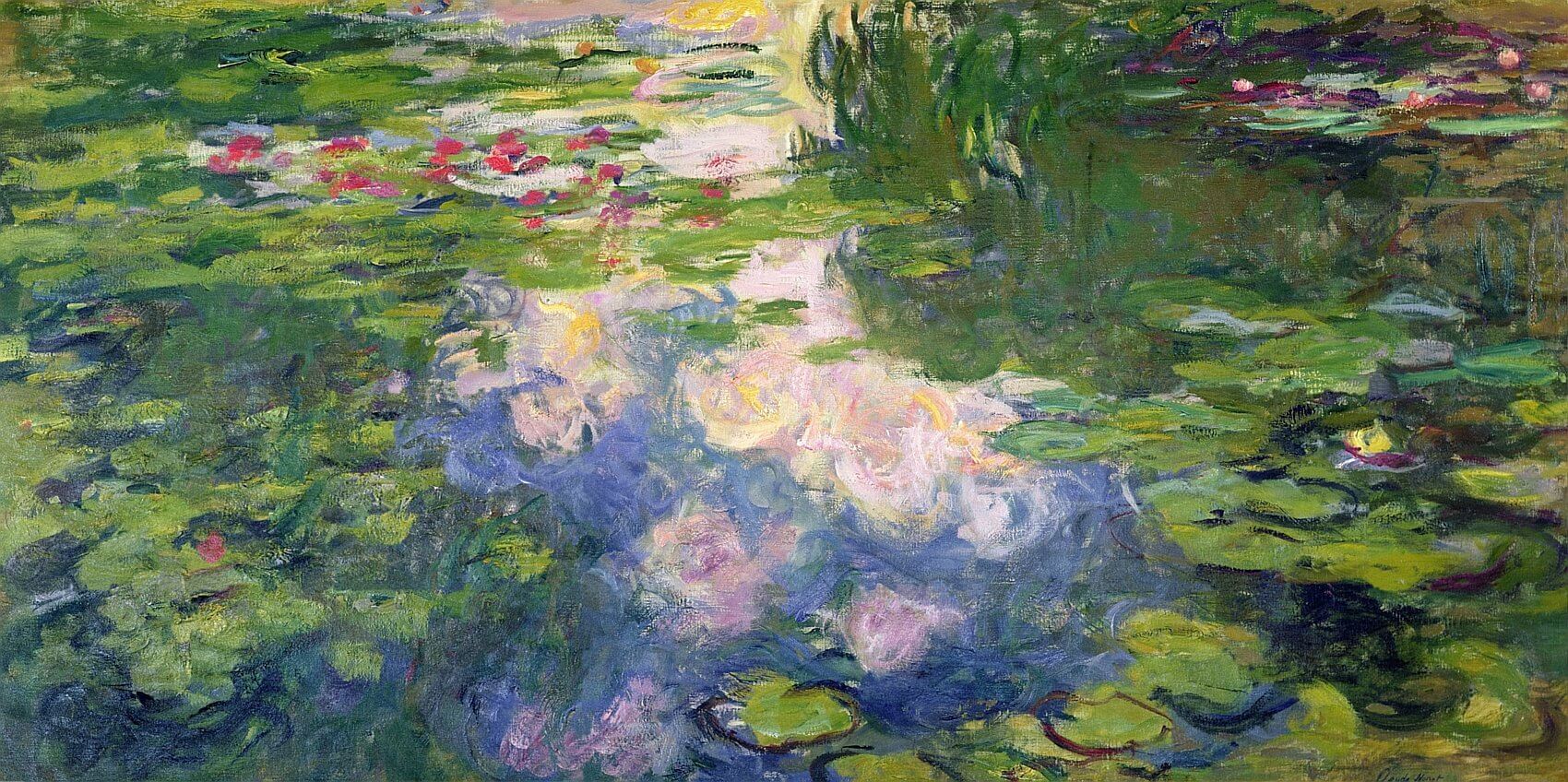

Technique 3: Embracing Uncertainty

If worry thrives on uncertainty, the next step is to learn to live with it. This doesn’t mean ignoring risks or pretending life is perfectly predictable. It means gradually discovering that ambiguity is survivable – and sometimes even enriching.

You can start by acting “as if” you are already tolerant of uncertainty. Ask yourself: "If I were comfortable with uncertainty, what would I do?"

This mindset allows you to face uncertainty instead of avoiding it, which is the most effective scientifically proven way to reduce anxiety long-term.

Exposure involves intentionally staying in situations that provoke worry until anxiety naturally decreases, without using avoidance or protective behaviors to eliminate the discomfort. Over time, these small acts provide proof that uncertainty does not always lead to disaster. Your mind learns that you can handle uncertainty and that anxiety will pass.

Example: Daniel

Daniel, a software engineer, checked every email twice, triple-checked reports, and micromanaged projects. Anxiety left him exhausted.

One week, he delegated a routine report to a colleague without reviewing it in detail. His chest tightened, and he imagined everything that could go wrong. But the report was completed successfully, and Daniel realized he could tolerate the discomfort – and the outcome was not catastrophic.

Weeks later, he gradually let go of more small controls. Each success built confidence, showing him that uncertainty could be managed.

How to Help Yourself: Tolerating Uncertainty Experiments

Try to complete at least one “tolerating uncertainty experiment” per week.

Step 1: Identify your anxiety-reducing habits

Make a list of behaviors you often use to reduce anxiety, such as:

-

Re-reading messages before sending

-

Double-checking work

-

Seeking reassurance

-

Over-preparing or avoiding tasks

Step 2: Start with manageable challenges

Pick one task from your list that feels slightly difficult but doable. Begin with small steps to ensure early success and build confidence.

Example tasks:

-

Send a message without rereading it.

-

Make a minor decision without asking anyone for reassurance.

-

Go to a movie or restaurant without reading reviews.

-

Ask a friend or colleague to help with a task instead of doing it yourself.

-

Pack for a trip without checking your bags multiple times.

-

Call a friend spontaneously to invite them out.

Step 3: Gradually increase difficulty

Once a small task feels manageable, move on to a slightly more challenging situation. The goal is to expand your tolerance slowly over time.

Why This Works

-

Anxiety passes: Each experiment shows you that anxiety can be endured and will decrease naturally.

-

Uncertainty isn’t dangerous: You’ll discover that outcomes often aren’t as threatening as your mind predicts.

-

Life becomes richer: Tolerating uncertainty opens the door to new opportunities and enjoyable experiences.

By practicing these exercises, you build confidence in your ability to navigate life’s unpredictability, rather than avoiding it or feeling overwhelmed.

Moving Forward

Uncertainty is an inevitable part of life, and it can feel deeply uncomfortable. I hope that the three CBT techniques shared in this article help you develop a healthier, more flexible relationship with it.

We rarely know what the future holds. What we can do is practice responding to uncertainty with greater awareness and confidence – trusting that we have the capacity to cope, even when outcomes are unclear.

Life is a balance between safety and risk, and that balance looks different for everyone. The task isn’t to eliminate uncertainty, but to find your own workable middle ground – one that allows both security and growth.

As John Finley once said, “Maturity is the capacity to endure uncertainty.” Learning to tolerate the unknown is a strength – one that makes space for resilience, possibility, and a fuller life.

References

- Springer, K. S., Levy, H. C., & Tolin, D. F. (2018). Remission in CBT for adult anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 61, 1–8. Read here A meta-analysis showing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders.

- Rnic, K., Dozois, D. J. A., & Martin, R. A. (2016). Cognitive Distortions, Humor Styles, and Depression. PubMed Central. Read here This study shows that cognitive distortions – negative biases in thinking – can increase depressive symptoms by reducing adaptive humor styles.

- Beck, A. T., et al. Cognitive distortions and cognitive therapy foundations. Springer. Read here Foundational work introducing cognitive distortions and their role in anxiety and depression.